Folklore, old Welsh knowledge and personal ideas of belonging to land and to place

Rhodri Owen

Cymraeg

A version of this piece was read at Pontio during the celebration event for Jess Balla’s – O’r Tarddaid I’r Tonnau. The purpose, I think, is to encompass some of my thoughts about water - it’s folklore and it’s history in the Migneint and Ysbyty Ifan areas, as well as my relationship to it.

I could expand further on each point made, but it’s worth leaving things open sometimes to hear the views and knowledge of other people. Over to you, get in touch with your thoughts.

I feel the need to seek out and do something with our own Old Knowledge here in Wales, and especially in my area around the Migneint and Ysbyty Ifan.

Although some of the stories are well documented in various books across the ages; many of the stories have gone with the generations.

Stories and names attached to land and water that were passed down from generation to generation in Welsh, have been displaced by the same forces of capitalism and colonialism that changed our society and ecology, here and elsewhere.

“A Gitksan elder from British Columbia when confronted by a government land-claim asked "If this is your land, where are your stories?" “

Ysbyty Ifan is split in two by the Afon Conwy high up in the Conwy valley, underneath the vast wet moorland of the Migneint. The Conwy gains some width by Blaen Y Coed where the Serw joins it in a place called Gweirglodd Y Telynorion.

Gweirglodd is “meadow” and telynorion is “harpists”. The story goes that a harpist was lured into a cave by the gorge where the Serw enters the Conwy – he was lured there by the music of the Tylwyth Têg and is trapped there forever playing his own song. And of course, the music can, and is still, heard there today on certain days.

I’ve never heard the music myself, but I’ve never found the cave either – but both are said to exist. Fishermen and farmers that aren’t into superstition and belief in fairies have said as much.

Although not publicly.

At more or less the same spot, or very near, at Trwyn Swch there exists a Changeling story, ending with the two swapped children of the underworld thrown into the water of the Conwy off the bridge, and the original two babies returned to the crib. Changeling stories have a dark origin, sometimes related to disability or mental illness and the faerie swap being a primitive way of explaining it.

The word Swch means a plough and refers to the shape made by the confluence of the two rivers.

It, and the harpist story, probably also serves as a way to keep the children of Trwyn Swch and Blaen Y Coed from the wild torrent of the chasm where the Conwy flows. The river in this case being the home of the Tylwyth Têg.

Way down the valley there is the story of the Gwyber of Wybrnant, the flying serpent that terrorised the valley – a story which ends in the triple death of the hero as predicted by a Dyn Hysbys. Triple deaths being a worldwide motif - Vedic, Germanic, Celtic and Roman amongst others, if not even earlier.

It is noted in a newspaper article from the 1800s that there was found a notebook in the eaves of the house at Hafodyredwydd, Penmachno relating to the ancient monastery and hospice at Ysbyty Ifan. It was written in Latin and was a count of the fish stocks transported from Italy to Llyn Conwy by the Romans. I could not find any mention of this anywhere else, nor has anybody heard of such a thing. It does seem unlikely on many counts, but I have taken it into my own folklorisation of the area none the less.

Downriver the well known legend of the Afanc exists - the mythical afanc lived in a pool on the Afon Conwy and caused vast floods – eventually dragged away by Ychen Bannog with iron chains into Llyn Glaslyn by Yr Wyddfa.

Ychen Bannog were strong otherworldly oxen and Llyn Llygad Yr Ych – the lake by Moel Siabod, was created by the popping eye of one of the straining oxen on its journey towards Bwlch Rhiw’r Ychen and on to Glaslyn.

Today, the peat in the water of Llyn Llygad Yr Ych or Llyn Y Foel, means there is a version of brown trout in the water that is unique to anywhere else. The lake itself drains into Afon Ystumiau, then into Afon Lledr that flows through Dolwyddelan towards Afon Conwy.

The afanc, as in literal beaver, had been killed off in this land when this story got transcribed, and the imagined descriptions of it have made it into a creature akin to a crocodile - with fangs, scales and of a huge size. Why was there a need to invent this creature... if indeed it was invented?

Notice in the story that the Afanc isn’t killed, it is only moved elsewhere - a lesson or warning about the effect of moving nature by force maybe? The mention of the iron chains loosely connects it to the Tylwyth Têg and the mythical taboo of being hit with iron. The Tylwyth Têg are not to be touched with iron!

On the outskirts of Ysbyty Ifan there’s a Chalybeate and Sulphur well that used to be a place of congregation a few generations back, the water was believed to have healing qualities and was especially good for arthritis and treatments of warts on hands. It was also known that the water in the trough at the forge in the village – rich with iron from cooling forged materials – was also a cure for warts.

It used to be that the children of nearby Tŷ Nant were baptised with the water of the iron rich well.

As part of my work with Gofod Glas, I started talking to a fisherman in Dolwyddelan – Eurwyn Pencafna.

I filmed him tying a fishing lure used on the Lledr for decades – y Bajar Goch, named as such because it uses fur from a badger and fibres from a swan’s feather dyed bright red.

I also recorded a preliminary interview with him where we skimmed over topics related to his own knowledge and experience of fishing and local rivers.

Sadly, Eurwyn died a couple of weeks later.

Eurwyn, at 75 years old had fished in the Lledr and his favourite, the aforementioned, Afon Ystumiau - for most of his life.

The further questions that I had been meaning to ask this keeper of knowledge (though he himself might not have called himself that) remain unanswered, though I will take them and the whole conversation wit Eurwyn to the community in Dolwyddelan for further discussion.

My previous work with Gofod Glas involved interviewing a handful of people who are named after rivers or lakes in the Afon Conwy area – namely Eidda, Serw, Euarth and Llugwy, and mostly from agricultural backgrounds. I took them to the banks of their rivers or lakes and asked them what their connection to the water was, amongst other questions.

I also asked the newly popular question “Is a river alive?” – with no context and no preamble about the then unpublished Robert MacFarlane book of the same name.

Two said yes and two said no. All were certain.

They all also believed “their” river was clean. They proudly carry the name.

There existed a village, and a mill, in Ysbyty Ifan long before Lord Penrhyn got his wiry hands on the place of course, but the postcard houses you see now were built by the Penrhyn Estate around 1870, when the gentry had gamekeepers breed the grouse for shooting amongst the boggy peat and the brwyn.

--

My family on my father’s side came here four generations ago, on a horse and cart from Abergeirw. Carpenters all the way back - Griffith Owen becoming a wheelwright in the village and my dad Huw Selwyn Owen carrying on with that craft and moving on to furniture making having seen the end of the wheelwrighting country carpenter era. I eventually took on the craft as a furniture maker too. Living and working by the same flowing Conwy that turned the water wheel that was central to community life.

Before the 1500s, the bridge over Afon Cletwr was the Eastern boundary into the parish of Ysbyty Ifan, which at the time was a place of sanctuary under the protection of the warrior monks of St John – the hostel there giving alms to pilgrims on their way to cross Y Swnt to Ynys Enlli. By crossing the river into Ysbyty, the law here was separate.

“Caled fu ar lawer gŵr cyn croesi Pont Y Cletwr

A hard life for many a man before crossing Pont Y Cletwr”.

This led, if another landowner - Wynn of Gwydir is to be believed, to Ysbyty Ifan becoming a “den of thieves and murderers” as the local bandits took advantage of this sanctuary.

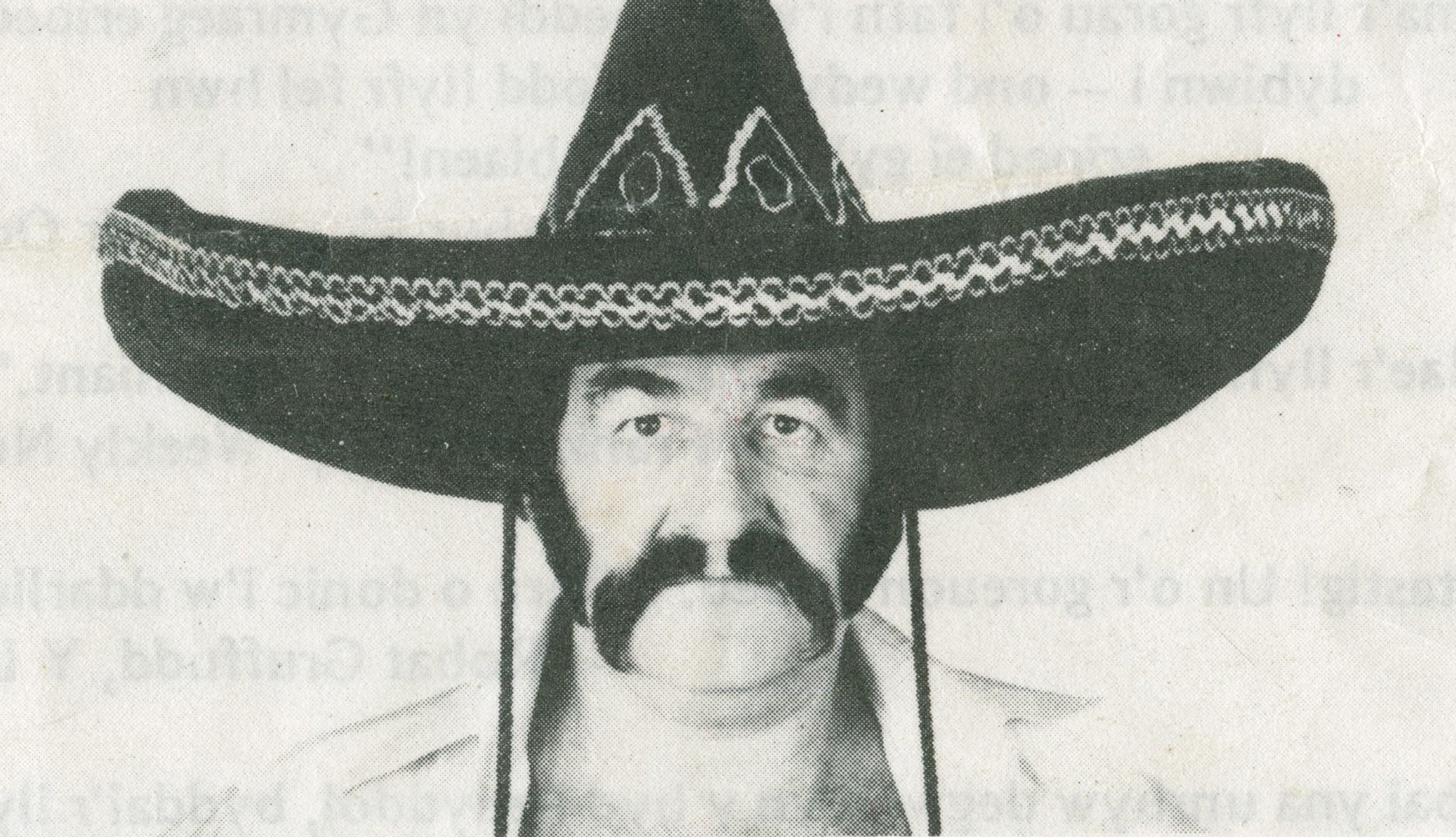

It is also the reason the Ysbyty born, modern folk hero and professional wrestler Orig Williams named himself El Bandito

In August of 1846 there was a huge storm. The brunt of which was emptied onto Ysbyty Ifan – the country inundated with water for miles around. On the same night lightning came down the chimney of a house on Anglesey and knocked the sitting couple off their chairs.

On that night, above Y Gylchedd, the clouds burst. The torrent of water causing a landslip, the scars of which can be seen today. The peaty earth was carried violently down the valley via Nant Llam Gwrach down towards Afon Cletwr, carrying with it 4 of Cerrigellgwm’s cows and sweeping away most of the workings of the Cletwr woollen factory that stood beyond the bridge on the banks of the river – waterwheel, cows and all - all swept into the Conwy.

On the same night, there is a vaguely remembered story of a midwife on her way across the mountain from Bala to Ysbyty to attend to a pregnant mother, sheltering for her life from the raging storm under the peat hags.

From an obituary in 1916, there is mention of a Jane Roberts who “had lived here weathering the storms, having been born the night of the great landslip on Y Gylchedd in 1846”.

Caletwr itself, meaning hard river – referring to the fast flow – was incidentally named in the early 2000s as one of the cleanest rivers in Wales. (though I could not say how it is now).

There is nothing much by the bridge today except an old electric turbine fitted in the 1960s. No sign of a woollen factory, or of the mini-industry that grew around it except for the handful of houses, derelict and otherwise, at the top of the hill. No bandits either.

But Afon Cletwr still flows.